Does word exist if we are not making it?

What does it take to make sense of the world around us?

I would spend days watching those vast, probabilistic engines of text, churn out what they think is sense. Contrary to most people's expectation, the current wave of generative AI doesn't simply challenge our definition of intelligence. Rather, it forces us to confront a fundamental failure of our own language (however unintentionally here, I used a common contrastive negation that they love to use).

Machines don't really perceive or sense. That much is clear when you peer behind the curtain. What language models do is essentially map the sprawling chaos of human writing, image pixels, and sound waves into dimensions of vector embeddings. Every word, every token, is just a point in an N-dimensional space, positioned by its statistical history of the training data.

It's a beautiful, terrifying sleight-of-hand. The LLM processes these smoothed, continuous vectors and projects them back into the hard, discrete boundaries of human-readable symbols. This transition, from the flowing vector space back to the rigid word, necessitates aliasing, a loss that we have to accept every time we hit enter after typing some poorly formatted strings in a chat box.

Here's the strange, almost ritualistic behavior I've noticed in myself and colleagues: when we question, complain, or curse the machine for producing nonsensical garbage (or "hallucination," as the engineers call it), we have already granted it a soul. We assume it can think, that it understands our frustration at its failure to cohere with reality. It's an almost innate, almost universal habit to treat the machine like another person, attempting to parse words we ourselves did not make. And we're left with the hollow feeling that a word without sense is like a world without substance. It's the Turing Trap revisited: we accept the output because we need the illusion of interlocution.

Can we formalize the world without these symbolic references? The question always brings me back to the filmmaker Harun Farocki. Early in his series Parallel II, where he explores the genesis of computer graphics, he asks: "Does the world exist if we're not watching it?" Farocki was asking about the computer's synthetic gaze, but the query is equally potent for LLMs, which operate on a purely textual representation of the world.

There's a history to this tension, i.e., the decades-long cognitive science debate over mental imagery. In the 1970s, it was a philosophical brawl. Was a mental image a literal internal picture (Kosslyn's pictorial view)? Or was it just a descriptive, sentence-like representation stored in a language of thought (Pylyshyn's propositional view)?

In the human mind, the pictorialists ultimately found support when neuroscientists saw the visual cortex light up during imagination. We seem to sense the world, then we name it. Sensation precedes symbolic reduction. But the machines are the ultimate Pylyshnian dream. Their reality is a pure propositional substrate. The vectors are just compressed, high-dimensional descriptions. When a multi-modal AI processes an image, it isn't "seeing" a cat, purring or stretching in the sun. It's correlating the text vector for "cat" with the text vector for "meow" and the numerical vector of RGB values that its training data has already labeled "picture of a cat. An extremely efficient, un-human way of cross-referencing.

Yet, our human impulse is to project our own experience onto it. We think, "If it can describe the cat so vividly, it must see the cat." This confidence that machines are replicating our mind is born of a profound cognitive capture, where we confuse statistical fluency with ontological understanding.

Machines don't really see; however, they are astonishingly proficient at generating a lexicon of vision. They generate perfect captions and stunning images based on verbal prompts. Words, in effect, compensate for the machine's Achilles' heel: the lack of embodied, continuous sensation. The curious parallel, though, is that we humans share an almost blind, instinctive drive to reduce worlds into words. It's an impulse toward epistemic closure. We want to pin down the unruly, continuous flow of reality with the clean, discrete boundaries of language.

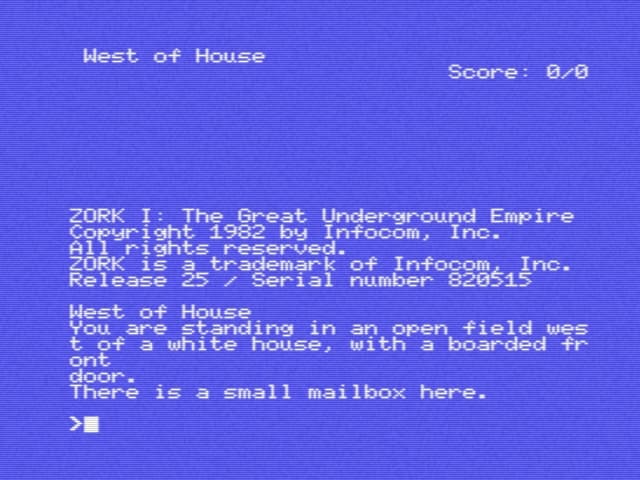

Think back to the old text adventure games like Zork I. The world only existed through your input: 'TAKE SWORD,' 'GO NORTH.' If you typed, 'LOOK UP AT THE VAST, PURPLE SKY,' and the programmers hadn't included 'PURPLE SKY' as a recognized object or attribute, the world literally ceased to exist in that moment. It was a digital existential crisis, confined by the vocabulary. The analogy stands with modern AI. We haven't changed much. We willingly subject ourselves to the machine's "field of vision," modeled on our own neural complex, only to discover this prosthetic vision is leaving us crippled. ((By the way, now even AI plays Zork!!)

The core theoretical obstacle, what I call the Vector-Symbolic Gap, remains. Classical AI was logical. A word was a symbol with a fixed referent. Modern LLM is probabilistic: 'king' is near 'queen' and 'man' is near 'woman' in the embedding space because that relationship appears often in the training data. This system knows the internal statistical relations of symbols, but it has no necessary external relation to the world. As Hubert Dreyfus argued decades ago, any system that lacks embodiment and common sense (i.e., a situated background) is doomed to a kind of abstract competence.

This is why the term "hallucination" is so misleading and, frankly, dangerous. It's an anthropomorphic distraction. When an LLM confidently asserts that "The Eiffel Tower was built by the ancient Romans," it is simply executing its function with perfect statistical integrity. The vector space, having been trained on billions of tokens, has placed "Eiffel Tower" and "ancient" (or "great wonder," "historical landmark") in a proximity that is statistically strong enough to be selected, despite the proposition being factually incorrect. It is a sampling artifact, albeit however delusional it might sound. My proposal is to replace that lazy term with "confabulatory interpolation". The machines are performing a high-confidence, statistically coherent lie. This is the fidelity of the statistical model, and it underscores the true problem: the machine doesn't really care about truth.

The quality of the LLM is entirely determined by its corpus, the massive training set. It is Borges' Library of Babel finally realized, where all possible sentences are theoretically present, but the algorithm's job is to efficiently retrieve the most likely ones. The old GIGO principle ("Garbage In, Garbage Out") is far too simple. For LLMs, it's closer to "Bias In, Bias Out (BIBO)." The data is overwhelmingly biased towards English, corporate archives, popular internet text, and easily digitized documents. This bias is amplified and structurally embedded within the very geometry of the vector space.

This operational text creates a crisis of the first-person perspective. The LLM speaks with the voice of every author, and therefore no author. We are losing the courage to pursue the singular path through language that defines our individuality. We are being reduced to highly variable, but ultimately replaceable, data points in the grand semantic field. The true answer to Farocki's updated question is this: Words can exist without human authorship, but they are hollow. They are statistically perfect shells of meaning, lacking the intentionality and referential grounding that only a situated, embodied, sensing, and fragile human consciousness can provide.

We have to choose the difficult path. Our task is to use the machine's very existence as a mirror to reaffirm the specific, non-replicable value of human symbol-making. We must emphasize the somatic, situated, and resistant nature of true human language. We must push back against the ambient language by seeking out expressions that are so specific, so improbable, that they defy the predictive model. We must choose, once again, the painful, difficult word to save the substance of our world.